Annotating genes sequences with data from herbarium sheets and publications

Linking molecular data to taxonomic names and their extensive taxonomic treatments represents a fundamental component in biodiversity assessment. Voucher specimens for sequenced data can be the key nodes to make these connections.

— Project 15, Biohackathon 2021

Taxonomic treatments are research results related to a taxon published in a standard way as sections of a publication. Ideally, and in the context of reproducible science, all the data or identifiers to the data are available. For taxonomic publications “all the data” include material citations to the specimens used and genomic data generated as basis for the analysis. Thus a curated link is provided in a publication between a species, more precisely a taxonomic name providing the expert identification of a specimen, the specimen itself represented by its material citation, and one or more DNA sequences. Furthermore, the taxonomic name can be linked to the cited treatment, opening up further data about the species. The treatment includes other data such as traits that can be used to annotate gene sequences.

In an ideal world, the linking within the treatment can be used to either start from a specimen or a gene sequence to discover more information about it such as its geographical range, the source specimen, or its location in the phylogenetic tree.

This would require these relationships to be explicitly expressed in the publication, or at least available for machine-processing — how else could we process millions of printed pages? The natural candidates for expressing this relationship are either the material citation that includes the data about one specimen or tables that include all these data in one well organized location.

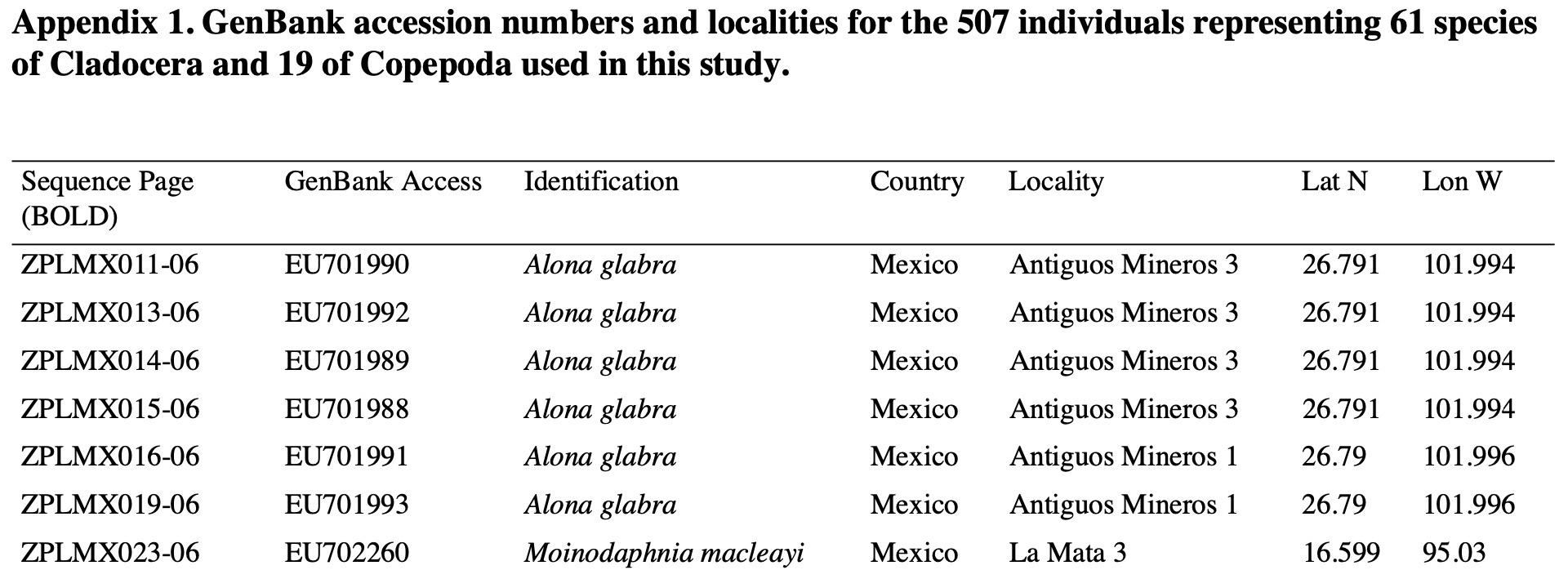

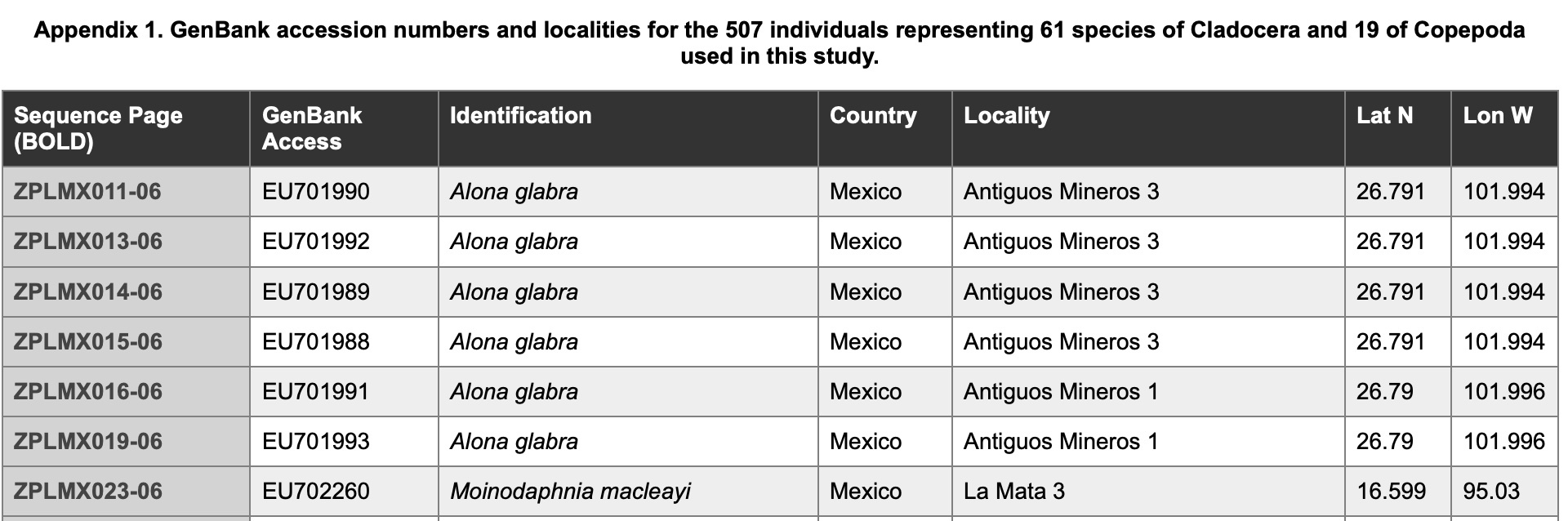

The reality however is that an increasing number of tables are produced listing the specimen and its gene accession numbers or the specimen code or geographic location information. This would be reasonable if tables were not hard to extract, especially if they span multiple pages, and then to provide the rows as material citations representing the links between specimen and genes.

The other reality is that many of these tables are published as supplementary material in the form of MS-Excel or MS-Word formatted documents, without identifiers and thus can not be automatically discovered, extracted and analyzed programmatically. Of course, the publications that are behind paywalls do not even allow reuse of the data without institutional access or upfront payment

In this hackathon, we focused on the most promising source for specimens– and genes– related data to find and extract tables, and check them for quality. We analysed 14,000 tables already extracted by TreatmentBank to develop a quality control mechanism for determining the correctness of the extracted tables, and are now continuing to develop a more refined mechanism to represent the quality of extraction.

This work is based on TreatmentBank’s algorithm to extract tables, even tables that may span multiple pages, and deliver them in different formats such as JATS.

The results are very promising. We continue to work to make tables first-class digital citizens and extract the respective data as citable units, ultimately accessible in GBIF as material citations that express the relationship of genomic data with specimen and literature-based data. With this, we will be able to close the gap between specimens, genes and literature and provide an expert-curated link between them.