Liberating material citations as a 1st step to better data

Our colleague Prof. Roderick Page recently wrote about quality issues with the data we are extracting from scientific literature and making available for anyone to use anywhere for any purpose. We are thankful for Rod’s insightful and helpful criticism. In this post (and several others to come), we explain material citations and other data that we extract, address the data quality issues — why they exist, what we are doing about them — and why the extracted data are still important and useful despite the inherent errors.

Material citations are one of the data types in taxonomic publications that spur a lot of interest and discussions. They cite the specimens used for the research, linked to a specific taxon, either by being included in a respective taxonomic treatment, table or supplementary materials. They represent the expert’s identification of the specimens, and because of that, are the best possible documentation of the identification of a specimen. This is unlike many digitized specimens from natural history collections that have not passed expert curation, peer-review and publication in scholarly articles, especially revisionary works. The person who identified them as well as the source of the citation can always be tracked with their respective links to the treatment. This kind of material citations are highly valued because of their richness of facts. These facts can include the collecting location, country, habitat, collecting methods, collector, collecting date, and specimen code. Because of this, they play an increasingly important role to answer questions such as who collected where, when, what, or which specimen has been reused.

As pointed out in the Plazi symposium at the TDWG 2021 conference, the “key bits of information” produced by TreatmentBank, complementing named entities such as taxonomic names, are taxonomic treatments, treatment citations and figures that are extracted mainly from PDFs, made FAIR and thus made ready for human and machine consumption.

Materials citations are a downstream product in Plazi’s workflow, especially the parsing of details, as part of the treatment and the source publication. We recognize their availability in this format as highly valuable for third party processing despite all their shortcomings, providing unique data especially for less known species, and in collections not yet digitized. While less than 100% accurate, they hopefully contribute to developing best practices on how to publish specimens in the future.

The data quality problems with materials citations are a result of many reasons – for one, they cite one or more specimens in a highly variable way and are embedded in unstructured text. Additionally, OCR procedures, especially of PDFs scanned from historical publications, are prone to a relatively higher amount of errors. At the moment they are published for humans to read and understand, but certainly not for machine consumption.

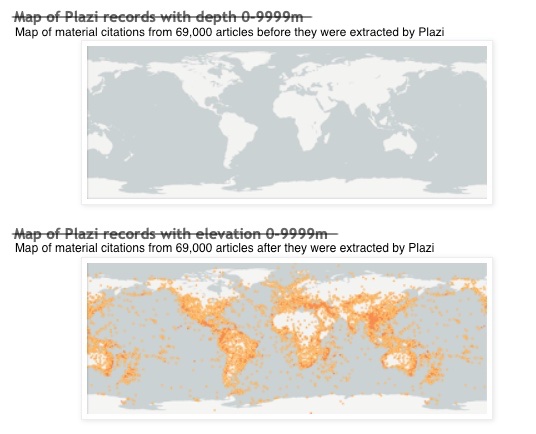

In spite of all these quality issues, we believe there is value in extracting and liberating materials citations. Open and FAIR data lend themselves to further refinement, or to build applications to visualize annotations in text, reuse them on maps, or display them as individual occurrences with rich metadata such as by GBIF, or be reused by other publications (Plazi mediated data is used in over 500 scientific papers). For this, we need to not just improve the quality of the extracted data but make the data more structured and extractable to begin with. The recent collaboration between the European Journal of Taxonomy, Pensoft Publishers and Plazi led to guidelines on how best to publish material citations.

Treatments and material citations of up to 80,000 species are the only source of information about these taxa in the Global Biodiversity Facility (GBIF), indicating the important role of research publications to understanding the long tail of little known species.

Quality control and feedback mechanisms help improve material citations. We believe that 1 million liberated and usable material citations is an important first step despite the errors inherent in the test mining process. Material citations are part of a treatment, and thus the taxonomic identification is not an issue. The omnipresent link to the treatment and article and TreatmentBank allows curating individual material citations. We continue to work on QC issues and evolve this process to accommodate large scale, algorithmical curation. Ongoing developments to label the granularity of markup and quality control, together with increasing involvement of users, will make material citations fit for more use cases.

No machine translation, especially that of printed literature meant for human-consumption, is going to be 100% accurate. But the scale of potentially valuable data trapped in articles necessitates machine translation as the only viable way to liberate this data and make it available for secondary use. This will and does result in data that are not 100% accurate. Just like any other un- or partially-reviewed source, the material citations should be verified before further use, especially for further research, by comparing against the original text. To facilitate this, the material citations are submitted to an initial quality control stage on TreatmentBank, and we provide links back to the original text making data verification easy. Providing millions of facts in an easily searchable form allows for valuable analysis and synthesis over a vast quantity of research previously impossible. Making the data available results in an inevitable compromise in accuracy but not making it would result in a 100% inaccuracy by way of a complete gap in knowledge about them.

We continue to make investments in data QC that will lead to better quality, but we need crowdsourced human-curation from all interested users. In keeping with the spirit of open source that there are fewer bugs when many more eyes are looking at it, this trade-off between data availability and accuracy is hopefully temporary. Increased data availability will lead to increased use which will hopefully lead to increased reporting of inaccuracy that we will fix. The overall result will be beneficial to everyone.